A toolkit for compiling schemas to user-editable embedded device configurations

Background

Over the past few decades, the world of open-source electronics has blossomed into rich ecosystem of resources available for use by everyone, from hobbyists to electrical engineers. Open-source embededded programming environments, low-cost development boards, break-outs for sensors, electro-mechanical devices and more, software libraries for interacting with these external components, and connected web services have all made rapid electronics prototyping possible–with progressively less time, money, and knowledge.

For example, with relatively little knowledge, it is possible to rapidly design and build a battery-operated humidity and temperature sensor using a microcontroller with an integrated battery port and charger, a bus-enabled sensor, and example code that takes periodic measurements and sends them to a data display service over wifi. This project takes a few hours, and costs less than $50 total in parts. (This project was a real father-son project; we’ll refer to it several times throughout this post.)

But obstacles remain in translating a sensor prototype like this into a usable device or product. This post explores the design and implementation of serial-config, a toolkit for electronics prototyping that resolves some obstacles around user-friendly configuration of electronic devices.

Enter: Serial-Config

Serial-config is a software tool that supports field-configuration of devices by non-expert users. It turns structured data on a device into a form that can be edited from a desktop computer, using an interface that looks like a settings menu or online survey (google forms, survey monkey). The software resources it generates manage most of the configuration process, from the user interface for editing settings, to the embedded library that updates and stores settings data. In between, it includes a protocol for transferring updates.

Serial-config is used by a prototyper during electronics development. Given a schema that describes a configuration, it generates two software resources to support field-configuration:

The first is a user interface that allows a user to explore and edit a device’s settings when the device and interface are tethered together. This currently runs on a desktop, but can be implemented in mobile and other environments in the future. (These are described in detail in the future work section.) The user interface program is written by hand, and dynamically interprets a schema into a visual interface that can edit an instance of that schema. One section, a navigational tree, supports selecting reference types in the schema instance; when selected, another section, an edit panel, supports reading and writing the primitive configuration values in that type. The interface has additional functions to scan for available serial ports and select the device (updates are currently implemented over USB); read the config instance; navigate and edit it; display feedback to the user about current status and edit validation; and write an updated config back to the device.

The second resource is an embedded library that lives within a client program on a device. It presents a typed interface to the client program; it represents and manages the configuration instance; it reads, versions, and updates the configuration data from non-volatile storage, in response to user or device edits; it manages over-the-wire updates to the configuration, and presents a drop-in routine to the host program to do so. Some of the library is compiled from the schema, but much is written by hand around an internal interface.

When tethered, these two parts connect and work together. Pairing them gives the user the best of two worlds: the user can edit the configuration from a more capable and resource-rich environment. A wire protocol transports commands for reads, writes, transactional commits, protocol synchronization, and error recovery. The library on the embedded device supports configuration while using minimal resources.

Neither resource is competitive with hand-written software. For the user, the interface is user-friendly, and follows familiar and established interface patterns for editing settings. (This is a significant improvement over editing fields in embedded source code, or having no configurability at all.) For the prototyper, serial-config is efficient and conserves weeks of development resources: the features that serial-config supports are intensive, in the time, money, and expertise needed to build them; important, in the rich functionality they enable for electronic devices; and mundane, in being relatively uninteresting to work on and think about.

This initial version implements one complete strand across a common environment: the arduino microcontroller family, an electron-based desktop interface, updates through serial over USB, and storage in a microcontroller’s non-volatile RAM. In future versions, many modules can be implemented for microcontroller environments, transfer protocols, and interfaces.

A tension throughout the project is that microcontrollers have limited instruction and memory space; these resources are often too constrained for many of the strategies used in other software environments to achieve modularity, flexibility, and dynamism. This project uses higher-level descriptions created in fully-resourced environments to compile compact, project-specific instances.

Using Serial-Config

Specifying a Schema

The process of using serial-config begins with specifying a schema that describes the configuration. This is done in a python, using a collection of lightweight schema classes. This is what the schema might look like for our humidity sensor (a wireless network login, and an interval setting for readings):

import serial_config as sc

string = sc.List("string", sc.PrimitiveTypes.CHAR.value, capacity=255)

wireless_settings = sc.Struct("wireless_settings",

sc.fields(network_ssid=string,

network_password=string))

sensor_settings = sc.Struct("polling_settings",

sc.fields(poll_interval_mins=sc.PrimitiveTypes.UINT16.value))

schema = sc.Struct("humidity_sensor",

sc.fields(wireless_settings=wireless_settings,

sensor_settings=sensor_settings))

The schema’s root collection is a struct, with two subfields for wireless settings and sensor settings; the sensor settings structure is a number of minutes specified as an unsigned 16-bit integer; the wireless settings structure is a network ssid and password, which are both character strings no longer than 255 elements.

Editor Interface

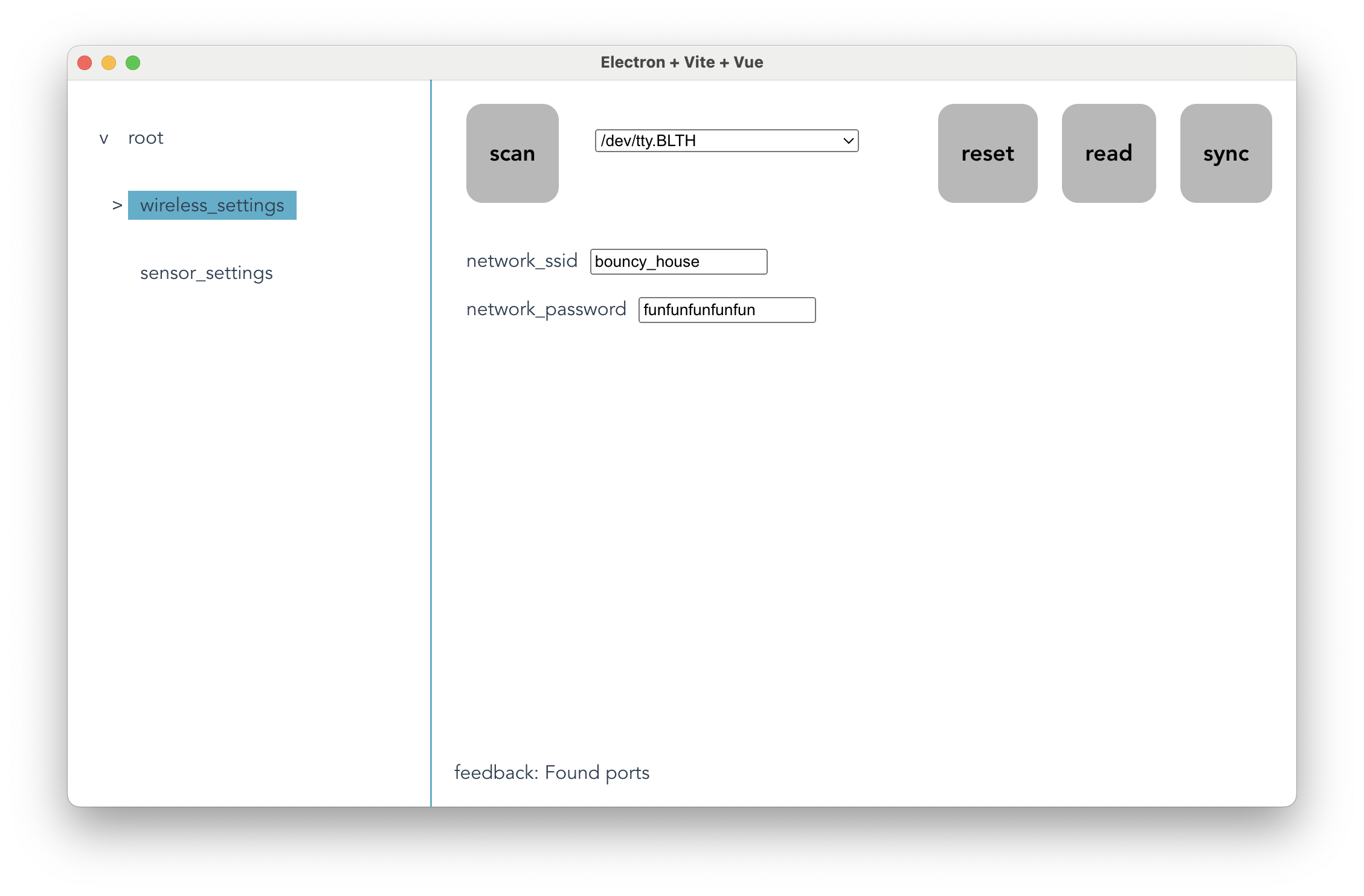

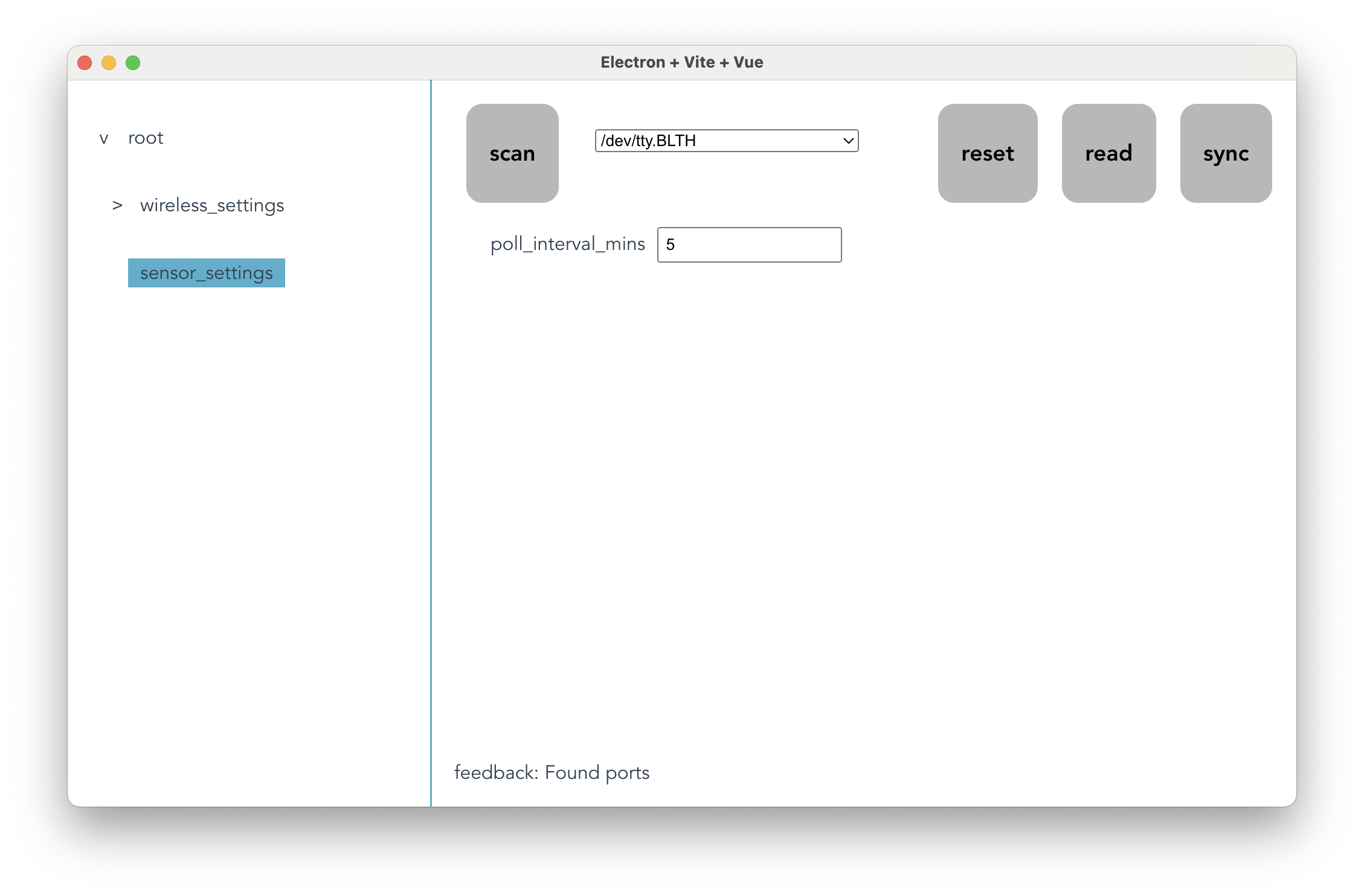

From this python schema, serial-config generates an equivalent json version of the schema, which is interpreted by a settings-editor interface. These are two panels of an editor for the schema above:

The interface is the same for all schemas. In the strip at the top are functions that manage interactions with the device. To the left, a button and a drop-down scans for devices and selects one. To the right, buttons read the configuration from the device, write it back, and discard edits.

On the left side of the window, a hierarchical navigator lets a user explore and select collection-types in the schema.

Once a navigation label is selected, its contents (primitive fields) display in the central panel, where a user can edit them. Edits are validated against the type: lists have lengths, numbers have limits, etc.

While not shown here, lists of primitive and collection types have controls for adding or deleting entries, and moving them within the list. (The strings shown for the wireless ssid and password are a special case of list display, where a list of type char is displayed and edited as a single string.)

At the bottom, status updates for device interactions and edit validation are displayed.

Embedded Library Generation

For the embedded library, serial-config generates a typed interface that is equivalent to the configuration schema at the start of config.h:

struct string {

const size_t capacity;

size_t length;

char list[255];

};

struct wireless_settings {

const struct string *network_ssid;

const struct string *network_password;

};

struct polling_settings {

uint16_t poll_interval_mins;

};

struct humidity_sensor {

const struct wireless_settings *wireless_settings;

const struct polling_settings *sensor_settings;

};

This is available to the client program, along with a series of routines for retrieving an instance, committing edits, and checking for protocol updates. Implementations of these are described below.

Serial-Config Implementation

Schema

The schema structure and types are represented by a collection of lightweight classes in python. Two collection types are currently implemented:

- structs are a key-value collection of field names and types

- lists are a capacity and an element type

The schema does not support self-referencing types. Primitive types are represented as enumerated python objects, and carry their native data type label; most native numeric types are provided. A default value may be specifed.

Schema Compiler

The compiler produces three files–two for the embedded library, and one for the user interface.

The config header (config.h) forms the interface to the embedded client program. Most of the header file is hand-written, aside from the schema-specific type signatures. A compiled portion at the top declares native data types equivalent to the schema’s structure.

The config implementation (ardconfig.cpp) manages the configuration instance on the device. The compiler stitches together two sections, one compiled and one hand-written. The compiled section has the instance allocation and its init code, the type and member labels needed for traversing the config, some defines used by the hand-written library (such as the root instance global), and the address look-up function. The hand-written section has code for an address resolver, configuration traversal, protocol parsing and interpretation, storage, interface functions, and local state.

The json schema is an analogous translation of the python schema into json. Little is done by the compiler: the python classes and types are translated into an object interface with labels, and some sorting and annotation is done on struct fields for straightforward access.

Embedded Configuration Library

A few parts of the embedded library are compiled: the declaration and initialization of the configuration instance, some artifacts about it (a reference to the root configuration instance and its type; the maximum depth of the configuration tree), and the accessor function that answers queries about collection member locations, sizes, and types.

The rest of the library is written by hand around these fixtures; the compiled parts present an interface that allows this code to remain agnostic to the schema. This part implements a translation of protocol messages into field reading, writing, and transactional commits. It also implements persistent storage, and retrieving the config for the client program.

Types, Instances, and Init

The native data types are a straightforward translation of the python schema. Struct types are named after the label passed to the schema, and contain the schema’s fields (these are primitives or references to nested collection types). Lists are represented as a struct containing a statically-sized array of their element type; primitives are inline arrays, while collection types are pointer arrays. The list structs also carry their capacity and current size.

One instance of the configuration is allocated statically in memory. It is defined in bottom-up fashion during init: static initializers set up default schema values, control fields, and hierarchical references. References and control fields (a list’s capacity) are important, and separate from updatable settings: these are are typed and initialized as const members, minimizing catastrophic misinterpretations by the client library.

This is what an instance and its initialization look like in the library implementation file for the humidity sensor:

/* INSTANCE */

struct string id_0 = {255, 255, {0, 0, ..., 0}};

struct string id_1 = {255, 255, {0, 0, ..., 0}};

struct wireless_settings id_2 = {&id_0, &id_1};

struct polling_settings id_3 = {0};

struct humidity_sensor id_4 = {&id_2, &id_3};

Variable names are defined in a bottom-up fashion; only the schema’s root instance is ever referenced by the library.

The instance is compiled to take up the maximum space possible for any variant of a schema definition. Lists statically allocate their entire capacity, and adjust their length field to account for dynamic changes. This avoids dynamic allocation and creates predictable memory characteristics for the client library.

Compiled Definitions

Much of the hand-written code needs to reason about the schema, despite not knowing what will be there. Explicit type and member labels provide this reasoning, along with a few other structures and macros.

Type Labels

Every distinct type in the schema is assigned an enumerated type label. Type labels are declared in contiguous sections, so categories for primitives, lists, and structs can be distinguished with internal, book-ending tags (IDENT__END_OF_PRIMITIVES). A matched array of byte sizes translates type labels into their sizeof value.

The type labels block for all the types in the humidity sensor’s schema looks like this:

enum ident_type {

IDENT_char,

IDENT_size_t,

IDENT_uint16_t,

IDENT__END_OF_PRIMITIVES,

IDENT_LIST_char,

IDENT__END_OF_LISTS,

IDENT_STRUCT_wireless_settings,

IDENT_STRUCT_polling_settings,

IDENT_STRUCT_humidity_sensor,

IDENT__END_OF_STRUCTS

};

Type Sizes

The matched array of type sizes looks like this:

const int ident_sizes[] = {

sizeof(char),

sizeof(size_t),

sizeof(uint16_t)

-1,

sizeof(struct string),

-1,

...

};

Collection Members

Members of collection types are assigned enumerated values, supporting the accessor scheme (explained below). For the root struct, this looks like this:

// Member accessor for struct humidity_sensor id_4

enum ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor {

ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor_wireless_settings,

ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor_sensor_settings

};

Defined Artifacts

A few other details from instance generation are compiled into macros for use in the hand-written section: the root structure’s field name, internal identifier, and type signature are used to type the library and start structure traversals. The structure’s maximum tree height is used for stack-allocation during a depth-first traversal.

#define ROOT_STRUCT_REF &id_4

#define ROOT_STRUCT_IDENT IDENT_STRUCT_humidity_sensor

#define ROOT_STRUCT_TYPE struct humidity_sensor

#define ROOT_STRUCT_TYPE_PTR ROOT_STRUCT_TYPE *

#define MAX_DEPTH 3

Altogether, these definitions support explicit inspection of the schema types, their member values, and their sizes.

Accessors

The accessor is the most important part of serial-config. It presents a uniform address space between the user interface and a tethered device, allowing for low-overhead reads and writes across a schema instance. It supports universal schema handling: much of the library code can vary little between schemas, and with minimal additional code size and memory usage as schemas grow.

Every field and collection in a schema is identified by an accessor path. This path is a numeric sequence that describes how to traverse the configuration to reach a field’s location, starting from the root structure. Within a collection type (struct, list, etc.), every member is assigned an index. For structs, the members are indexed by declaration order; for lists, the first three members are the capacity, type, and length, with element indices following.

In our humidity sensor:

- the accessor [1, 0] locates the

poll_interval_minutesfield - [0, 1, 0] accesses the capacity of the wireless ssid string

- [0, 1, 1] accesses the current length of the wireless ssid string, and

- [0, 2, 3] accesses the first character of the wireless password

The user interface can derive accessors from the schema for reading and writing field values, and sends the accessor with each protocol read and write command. The device can resolve accessors quickly, without look-up tables or recomputing as the schema instance changes; in the protocol design, accessor resolution is not synchronous and can take as much processing time as plausibly needed.

Accessor Resolver

The accessor resolver translates queries from schema-agnostic code into answers about the schema structure. Given a structure pointer, its type, and a member index, the accessor returns the member’s pointer, type, and size–or an error.

This is the accessor block for the humidity sensor’s root struct:

void accessor(void *treeref, uint8_t ident, uint8_t member,

void **value, uint8_t *value_type, ...) {

...

switch (ident) {

...

case IDENT_STRUCT_humidity_sensor: // accessing struct humidity_sensor

switch (member) {

case ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor_wireless_settings:

treeref = (void *) ((struct humidity_sensor *) treeref)->wireless_settings;

ident = IDENT_STRUCT_wireless_settings;

break;

case ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor_sensor_settings:

treeref = (void *) ((struct humidity_sensor *) treeref)->sensor_settings;

ident = IDENT_STRUCT_polling_settings;

break;

default:

goto broken_accessor;

}

break;

...

Given a pointer, its type tag, and the query member index (treeref, ident, and member), the accessor function jumps first to a type tag handler block (case IDENT_STRUCT_humidity_sensor:), then a member handler block (case ACCESSOR_STRUCT_humidity_sensor_sensor_settings:, for example). Each handler retrieves details about the member offset and type, and writes them back later in the function (**value, *value_type). Default handlers catch out-of-bounds members; the list handler checks the member against the array capacity.

Accessor-Derived Functions

The accessor resolver, along with the explicit type definitions, supports several important functions. The resolver forms the interface between code compiled from the schema and the hand-written library; it allows the hand-written part of the library to address, read and write, traverse, and store the configuration–while remaining agnostic to the details of a specific schema.

Field look-up: the protocol library is given an accessor path for a read or a write. Starting with the schema’s root object and type, the libary iteratively resolves the path’s next member index to a new pointer, traversing the structure until the path ends, or an error occurs. (In resolution, errors are not expected outside of protocol misalignment, though programming errors from the host are protected.) The accessor scheme supports lookups that are low-overhead, memory-safe, and reasonably fast. Aside from the accessor path itself, no additional memory (temporary or permanent) is needed to traverse the configuration structure; when the configuration is reconfigured (a list’s length is changed), no recomputing is needed. Memory-safety is enforced at the device-level by checking every path member.

The accessor look-up function, accessor_path, is straightforward:

void accessor_path(uint8_t *accessor_path, uint8_t accessor_path_len,

enum accessor_type access_type, void **value,

uint8_t *value_size, enum status_code *code)

{

void *finger = ROOT_STRUCT_REF;

uint8_t finger_type = ROOT_STRUCT_IDENT;

for (uint8_t i = 0; i < accessor_path_len; i++) {

accessor(finger, finger_type, accessor_path[i], access_type, &finger, &finger_type, code);

if (*code)

return;

}

*value = finger;

*value_size = ident_sizes[finger_type];

if (!ident_is_primitive(finger_type))

*code = status_code_write_protected;

}

Starting from the root structure, the function scans through the accessor path, resolving each member index to the next pointer and type until the end is reached or there is an error.

Storage: the library implementing storage is oblivious to the schema structure. To traverse the configuration, it incrementally scans across members until the resolver reports an out-of-bounds index. There are two passes for each collection type. In one pass, all primitive fields are written into the store (or read from it) and their sizes added to an offset; in a second pass, all collection sub-fields are recursively explored.

This storage scheme relies on the offset of every field being consistent across all variants of the schema; the library will first load a stored instance by scanning the init instance. This property is guaranteed by the memory layout of instance structures. Variadic structures (such as lists) claim the entire footprint possible across all schema instances. The storage code ignores data fields indicating current use (list length), and always walks and stores the whole footprint (list capacity).

The accessor scanning function, scan_config, is also straightforward (the iterator implementation for accessor_foreach is not):

void scan_config(void (*scan_fn)(uint8_t *, uint16_t, uint8_t), uint16_t offset) {

struct iter_ctx iter_ctxs[MAX_DEPTH];

struct accessor_ctx acc_ctx_inst;

struct accessor_ctx *acc_ctx = &acc_ctx_inst;

uint16_t address = offset;

accessor_foreach(acc_ctx, ROOT_STRUCT_REF, ROOT_STRUCT_IDENT, iter_ctxs) {

if (ident_is_primitive(acc_ctx->value_ident)) {

uint8_t *ptr = (uint8_t *) acc_ctx->value_ptr;

for (int i = 0; i < acc_ctx->value_len; i++)

(*scan_fn)(ptr, address, i);

address += acc_ctx->value_len;

}

}

}

The iteration macro accessor_foreach enters the loop for every field in the configuration. This loop body transfers to/from storage by calling a function, and adds the bytes to the total offset. This storage routine is used to commit an updated configuration to memory, or revert back to a previous version; this is done if an update fails.

Versioning: several instances of the configuration can exist in different storage slots. (The number of slots is up to the client and storage size; it is also up to the client application to use this feature. A straightforward use of slots is to always store a new configuration in the next slot, and revert to the previous or saved default if something does not work.) One headache of cross-compilation and diverse environments (8 bit, 16 bit, and 32 bit microcontrollers are encouraged) is that this slot size is hard to compute statically. Instead, this is done at setup time, using the scanning iterator walk the configuration and calculate the slot size.

By design, the accessor is implemented to minimize the amount of variable memory used and move as much information about the schema structure into instruction memory; microcontrollers tend to have more instruction space available. It also reuses the accessor function across multiple uses; a schema-specific compilation duplicates this information in the protocol and storage code, taking up more space. (The support code for the schema may be significant compared to this duplication.

Protocol

The serial protocol is designed to be compact, memory-safe, resilient against packet alignment and mis-programming, and easy to program and verify. The host initiates all interactions, and implements the complex aspects of the read and update state machines.

The host and data parsed from the protocol are not trusted by the device library to locate fields and write into them; all accessor paths are checked by the library, and all writes are sized and checked against a field’s data type size boundaries.

The packet frame

The packet frame is simple, and easy to implement in little code. This is especially true on the embedded side.

The host-to-device packet begins with an opcode, two length fields, two binary payloads, and a command separator (a newline). Most commands only need one payload, so the second length field is often zero. The read command sends the length of the accessor path in the first length field, then the accessor path in the payload. The write command similarly sends an accessor in the first payload, along with the write value in the second payload. The protocol currently does not use error-correcting-codes, though this is discussed in the future work section.

For example, a read for the poll_interval_minutes at accessor [1, 0] has a packet frame like:

<opcode read> <accessor length> 0 <accessor> \n

or

0x01 (read) 0x02 (accessor length) 0x00 (unused payload length) 0x01 0x00 (accessor) 0x0A

The device-to-host packet returns the host command’s opcode, a status code summarizing the command result, one length field, a payload, and its own newline separator. A successful response to the above read looks like:

<opcode read> <status code> <read length> <read data> \n

or

0x01 (read) 0x00 (status success) 0x02 (read of 16-bit integer) 0x05 0x00 (read data) 0x0A

This is some of the device’s protocol parsing code:

int opcode;

int slot_1_len, slot_2_len;

uint8_t slot_1[100], slot_2[100];

...

while (true) {

...

if (wait_for_protocol_header(hold)) {

// error ...

}

opcode = Serial.read();

slot_1_len = Serial.read();

slot_2_len = Serial.read();

if (slot_1_len > 100 || slot_2_len > 100) {

// error ...

} else if (parse_length_field(slot_1, slot_1_len, hold) ||

parse_length_field(slot_2, slot_2_len, hold) ||

scan_through_newline()) {

// error ...

}

...

// protocol handling code

This code is somewhat complicated by the timeout implementation, and its disabling with the hold variable. It begins by waiting for the first three bytes: the opcode, then the two payload lengths. Once the total packet length is known and has been checked, it tries to parse each payload, then the newline command separator. All parsing functions (wait_for_protocol_header, parse_length_field, and scan_through_newline) return true in the case of timeout.

Read and update workflows

Aside from read and write commands, a few other commands allow the host to form a resilient, transactional workflow.

The first is a marco-polo command: the host sends a random byte sequence to the device, and expects to see the same byte sequence returned. This ensures both sides are synchronized.

After reading the configuration, the host issues a hold command. When set, the update library waits indefinitely for follow-up writes; this allows the user to explore the configuration, make edits, and commit them to the device. This may be changed to a keep-alive command in the future.

The command set supports transactional logic for updating the configuration. The device and host implement compare-and-swap logic around a transaction id. The host begins an update by reading the device’s current id. The transaction commit command includes the current id; if this matches the device’s view, it returns an incremented id. This protects the device against errant commits, and allows the host to see if the commit succeeded; even if the return packet is lost, the host can recover from this by reading and comparing the current id. If any errors are encountered before the commit, the device restores the configuration from storage and returns control to the client program.

A recovery mechanism handles scenarios where the host and device encounter an error during reads or updates. Error reports are not expected in normal usage, but it is common in hobbyist electronics programming to print debug messages over serial; this may fill the host’s buffer with unrecognizable data when it firsts opens a serial connection. (Either party may also be misprogrammed.) If the host or device encounter an error, they issue a long synchronization sequence made up of 0s. Either party can start this sequence, and both expect the other to follow.

The string of 0s provides some hope of a recovering from mis-aligned buffers. The sync sequence is twice as long as any packet, and will transition a protocol parser out of payload wait. (1200 0s has been chosen as the sync length: 255 is the maximum length of a payload body. There are two, for 510 total bytes. 600 is a distinguishable sequence, and is doubled to account for possible payload consumption.) Once this occurs, a byte of 0 will eventually form the start of an interpreted packet; luckily, 0 has been reserved as an invalid opcode. Scanning into and counting this region of 0s can be done without additional memory, aside from the state as being in synchronization. After this sequence, any update must restart. If the device does not count this sequence, it will time out and return to the client code.

A Schema-to-UI Interpreter

The user interface program is written by hand, and dynamically interprets a schema to a visual interface that can explore and edit an instance of the schema. The interpreter is written in javascript, executing in the vue framework over node, and packaged for desktop environments with electron. (Bluetooth and mobile support are possible in the future.)

Every collection type in the schema generates two corresponding interface resources. The first is an editing panel that occupies most of the window, and displays the collection’s primitive values as editable fields. Edits are validated according to the schema type (integer, string, etc). List elements can be added, moved, or deleted. List of characters are a special case; instead of listing each element separately, these are presented as one text box.

The second resource is a labelled entry in the hierarchical navigation tree. This tree is placed on the left side on the screen, and allows exploration and selection of collections. This is a common paradigm from file system navigation. When an entry for a configuration is selected, its editing panel displays; the tree can fold/unfold; list elements are displayed by index.

Data Representation and Portability

One subtle implementation detail is around managing data values in a javascript environment that need to type and store across a variety of native architectures. There are two sources of data input and output: interface display and user edits, and binary reads and writes from wire communication. Both data sources have a collection of encoders/decoders that parse data into a common internal format from user edits and binary reads, and present it for user display or binary writes.

This internal format took some experimentation and careful design. In javascript, numeric values are represented as double-precision floating point numbers (64 bits); this can represent all floating point types on an embedded device, and a great range of integer types–but not all. The 64-bit integer type in C/C++ environments cannot be fully represented natively with a 64-bit floating point. Serial-config solves this by storing most integers in the interface as strings; integers are constructed using javascript’s BigInt object during edit validation and binary assembly, then converted into string. During binary writes, they are reparsed into BigInt, and written out in one byte numeric segments. Characters (char) are stored as their ascii numeric codes, and displayed as text.

The variety and ambiguity of data types across microcontrollers causes some additional difficulty. Most of this is eliminated by using type definitions from stdint.h, which bear the type’s size and sign; the interface’s encoders and decoders use these tags to validate and size data for writes.

The type labels for int and long are ambiguous. So are double and float; some environments implement a 64-bit double, while others use 32-bits for both. In some situations, the interface guesses at the size. In the case where the interface and device have mismatched data type sizes, the write will always fail and halt an update. (A prototyper will run into this during testing.)

An experimental (and currently incomplete) feature supports ambiguously sized types, for ints, doubles, etc: during read, the field size is sent by the embedded device, which has a static look-up table of all types in the config. The interface stores this byte size in the schema instance, where it supersedes the default size. (This is currently incomplete, because of some implementation complexity in updating list types. New list elements are created by duplicating the list element’s schema type; this type entry is never read from the device, so any byte length discovered needs to be updated in all list element type nodes above it. Finally, an empty list that is given an initial element in the interface is never read from the device.)

One future route to resolving this is to write a configuration schema whose only purpose is to gather useful architectural information, in byte sizes of various types and endian order. The results of reading this configuration schema form an architecture-specific size table, which can be stored alongside a schema.

The End

This has been serial-config. Schemas turn out to be very powerful. From one lightweight library of 3 python classes, along with some embedded support code and an interface interpreter, came:

- a user interface that can edit arbitrary schema instances

- a protocol that can move schema data to/from a device

- a typed interface for building a client program

- configuration storage, versioning, and more

Future Work

This initial version of serial config was an exploration of whether a toolkit like this was even possible! Whether this lightweight schema was expressive enough; if a well-designed interface paired with a simple compiler could work; if a generalized type interface, protocol, traversal, and accessor scheme was compact enough to fit onto a microcontroller; whether the user interface was easy enough to use.

All of these dreams came true.

But! There is more to do to add functionality and grow this project.

More Data Types

Lists, structs, and numeric primitives are an excellent start to the schema’s features, and cover many use cases. There are several more that would complete it.

Booleans and options/maybes: in an interface, these are simple radio buttons that a user can click; on a device, they set a flag (booleans) or indicate that a value or collection is valid.

Enumerations: on the interface side, an enumeration is a drop-down selection. (It is less necessary on the embedded side, this is just a number with an associated type tag; this function can easily be replicated with macros.)

Unions: C-unions support a structure that can be one of many types, and sets aside space for all of the possibilities. This is a complementary feature to enumerations; a union supports a drop-down selection associated with a collection of values.

Implementing this within the static allocation scheme will be tricky for collection/reference types, and needs design work. Because the memory footprint must remain static across all schema variants, the set of nested collections must take up maximum memory possible with any union selection. One strategy is to create a separate instance for each nested collection. Another strategy is to express each nested level of sub-collections as a union, preserving some memory space. Both strategies need to run a set-up function whenever variant is selected, that stitches the memory space together–this is done at init for all other types. Given this new set-up requirement, it may be easier to move the entire instance into a memory blob and the init into a library function.

More Domains

This project is a related idea to a previous project, PYES, which is a similar electronics development kit that focuses on the domain of flashing a selected embedded binary onto a tethered device; it creates a desktop interface with icons and descriptions of programs to explore and load.

Configuration and binary flashing are excellent initial patterns. Others are:

- data display and storage: many electronic devices capture data. A service for transmitting, displaying, storing, and exporting this data would complement a wide range of devices. (The Arduino IDE has a data graphing service that automatically converts logged data to graphs.)

- commands: the ability to execute a specific function on a device, controlled by a button or input form in the user interface, would be a huge advance. This is commonly used for controlling machines, and testing out settings (multi-color LED settings, etc).

- logging and tracing: embedded programs can be difficult to debug, because there are not enough resources to isolate the program executing and inspect its status. Debugging equipment is available, but expensive. A low-overhead logging and tracing framework, that transports debug information to a host, could help generate reports about issues.

- status and events: many embedded programs are implemented as state machines. Synchronizing the current status and transitions into a view for the host can support dashboards and state display.

UI File-Saving and Extensibility

The user interface is capable, but minimally so. Some development work can add useful features.

Configuration instances can be saved like files into folders, and re-opened and used later on. Default and other named/as-shipped configurations can provide good starting points.

The UI can be improved for extensibility:

- the navigation hierarchy is derived from the schema. This may be sparse for many configurations. The ability to specify display tiles that span collection layers and define what locations go on which page can give more control over the UI layout.

- while text boxes for editing are an excellent first step, not all configuration values are best edited this way. For example, a date/time value may want a date chooser. A color value may want a color picker.

Validation

This current setup has limited ability to support custom validation outside of a type’s natural size limit and list capacity. This is partly due to the awkwardness of expressing the schema and its compiler in python, while the interface runs in a separate javascript application.

There are a few options: one is to try and co-package python with electron; another is to support referencing validation functions written in javascript from the python schema environment, or adding validation code to the schema in javascript.

A third option is to design a lightweight validation language, and interpret it in javascript; it may also be possible to move validation onto the device, if there’s space for it.

ECC

The current protocol does not include error-correcting codes along with its payloads. For devices with enough program space, this would make transmission more reliable. Although not currently implemented, a lightweight solution is to read after writes, to double-check the corrent value is on the device.

Low-resource embedded library

The program size of serial-config’s embedded library is significant. Several things take up space: adapting the schema types and structure to an abstract method, supporting individual reads and writes to arbitrary addresses, and building a reliable, transactional protocol. These made serial-config easy to develop and debug as well.

Different strategies may make for a smaller, if less capable library. For many smaller schemas, a relatively small amount of code can update and store the configuration using known field offsets and sizes, and a single packet can read/write the entire config at once. This removes the need for the explicit type and accessor resolver scheme. Updates from the wire can stream into field values, instead of into a buffer.

Development and testing can show how the two approaches differ for different schema sizes. The current approach may be more efficient for larger schemas, while a fully-compiled approach may work best for smaller schemas.

More Embedded Environments and Update Protocols

Arduino is an excellent environment, but several others are popular. Raspberry pis, pi microcontrollers, circuit python, and rust are all possible options. Storage on sd cards and other media should be supported – this can support larger configurations.

USB is an excellent first choice for connecting to devices. Others are bluetooth, web servers hosted on microcontrollers, wifi, and an external server between the user and the microcontroller.

For interfaces, mobile is an excellent next step; an on-board touchscreen may be possible.

The compiler and internal interfaces will need some architectural work to support multiple environments, and expressing their selection. Some details of the schema format and the protocol may not be portable. For example, bluetooth assigns one address to each field.

Code Resources and Summary

The code for serial-config is located at: https://github.com/simonsbench/serial-config

Compiler

The compiler is located at https://github.com/simonsbench/serial-config/blob/main/serial_config.py

In general, for each section of the library file there is one global method that operates on the entire schema, and one corresponding method implemented on each schema class. The PrimitiveTypes, Schema, and List classes represent the three implemented schema node types.

The generate_config_header routine and generate_type_definitions schema methods produce the config.h library header file.

Several functions generate the library file:

generate_initsynthesizes the object instances and initsgenerate_accessor_enumsmakes the accessor enumerations for each collection typegenerate_identsmakes the type enumerations for all typesgenerate_instance_fixturesmakes the compiled definitionsaccessor_typesandstatus_codeshave the accessor types and status codegenerate_accessorproduces the accessor method

The make_js_schema routine synthesizes the interface’s config.json file.

Embedded Library

The hand-written embedded library is located at https://github.com/simonsbench/serial-config/blob/main/arduino_src/ardlib.c.part

accessor_pathresolves one accessor through the config treeaccessor_foreachiterates over every collection and primitive field;scan_next_iterrepositions the iterator in between loop roundsscan_configloads/stores the configuration from storagehandle_protocolimplements the protocol:wait_for_protocol_headerwaits until enough of the header has arrived to begin parsing,parse_length_fieldtransfers a payload into a byte array. With the opcode and payloads ready, the rest of the function jumps to the command’s handler. Successful commands loop, failed commands run thehandle_syncroutine, commits return and store the updated config, and cancels re-read the config- the rest of the file sets up the configuration instance and manages local state

Interface

The electron instance is stored in the electron_app directory.

electron/main/index.ts

index.ts implements the IPC calls from the interface renderer. It:

- loads the default

config.jsonschema from/static(get_schema) - reads the config from the device (

read_device_config) - writes updated fields to the device (

update_schema) - scans for devices with available serial ports (

serial_paths)

Schemas are prepared for reads. The next_read_accessor and find_read_accessors functions scan through the schema and find available accessors to read. This can be done in iterative waves, because lists need their length first, before any entries are read.

Schemas are also prepared for updates. The find_diff routine compares the last-read and updated schema, putting fields that differ into an update collection of accessors and binary serializations.

The SerialProtocol object handles most of the interaction with the device, for reads and writes. The handle_read method handles data receipt, and parses it depending on the current state; on success, the next command-response set is written with the corresponding command method. write_read_accessor handles a read command, write_change handles an update command, write_marco writes out the synchronization packet, etc.

For encoding and decoding, the read_definition and write_definition functions parse or write values between the schema’s javascript values and the binary wire values.

App.vue

src/App.vue implements the interface function. It defines the scan, port drop-down, reset, read, and sync buttons. It delegates interpreting the schema to the SchemaNode.vue component. It maintains the schema instance, and learns of edits through events that it applies to the instance.

SchemaNode.vue

SchemaNode handles the interpretation of one schema collection into a hierarchy navigation label, and its fields into an edit panel. When the navigation label for a node is selected, its display element is activated and its contents are teleported to the #panel label. Sub-collections are recursively interpreted by more SchemaNode instances.

Display*

The DisplayList, DisplayStruct, and DisplayDispatch components implement display of a collection’s fields. (DisplayDispatch is used when a list has a collection element type, and displays any of its fields in the list’s edit panel.)